The Psychological Impact of Light

You enter a room.

Before you consciously register furniture, colors, or materials, your body reacts to something else: the light.

Within milliseconds, your brain evaluates brightness, contrast, direction, and color temperature. That evaluation determines whether you feel safe.

Alert. Stressed. Focused. Welcome.

Light is not an aesthetic detail.

It is a neurobiological stimulus.

Why?

Because psychological impact is not static.

A space that activates in the morning should calm in the evening.

A workshop requires a different dynamic than a retreat area.

A hotel room functions differently than a lobby.

Why Adaptivity Matters

When we talk about light, we often talk about individual values.

Usage intelligence.

Daylight scenarios.

Human centricity.

Technical clarity.

Efficiency.

All of these factors are relevant. They can be measured, standardized, and compared. But when we enter a space, we do not respond to isolated parameters.

We respond to the interplay.

The diagram illustrates five dimensions of lighting quality. Interestingly, the strongest impact does not lie in sheer light quantity.

It lies in adaptability.

Light is most powerful when it is allowed to change.

Light Influences Our Energy Level

Light is the strongest external time cue for our body. It regulates the circadian rhythm, affects hormonal processes, and controls alertness, concentration, and regeneration.

Cooler, clearly directed light activates. It increases attention, supports analytical thinking, and conveys structural clarity. Warmer, softer lighting atmospheres signal relaxation, reduce internal tension, and support the transition into calmer states.

Yet what matters is not an absolute number or a fixed value. What matters is context.

A creative workshop requires a different lighting dramaturgy than a lounge or a private retreat. A hotel room functions differently in the morning than in the evening. An office with high communication density demands different conditions than a focused individual workspace.

What does this mean in practice?

• In the morning, the body needs clear, structuring light impulses

• During intensive work phases, directed light supports focus

• In transitional moments, softer contrasts ease mental shifts

• In the evening, warmer light tones support the hormonal transition toward rest

Static light contradicts our biology. Spaces should be allowed to breathe.

That is why we do not think in fixed values, but in transitions. In scenarios. In daily rhythms.

Good light does not only adapt to the space.

It follows the human being.

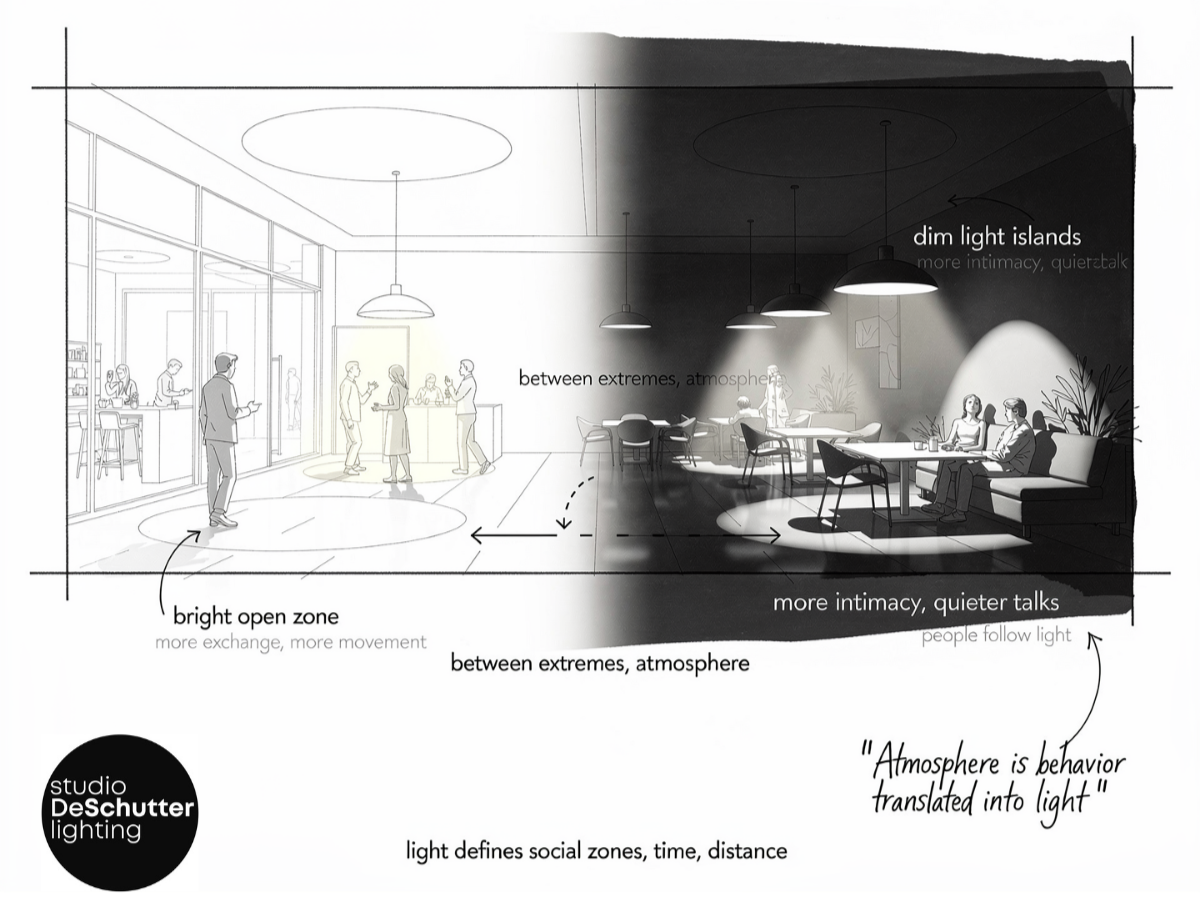

Light Shapes Social Proximity

Lighting does not only influence what we see.

It influences how we relate to one another.

Bright, open zones encourage exchange. People keep moving, interaction becomes more likely. Transparency creates dynamism.

Dimmed, clearly defined light islands, on the other hand, create intimacy. Conversations become calmer. Posture shifts. Voices soften.

People intuitively move toward the places where light invites them.

An overly bright space can feel anonymous.

A space that is too dark creates uncertainty.

What light does socially:

• It defines private and public zones

• It influences length of stay

• It shapes the dynamics of conversation

• It regulates perceived distance

• It creates belonging or separation

In hospitality projects, light determines whether guests linger or move on. In the workplace, it influences whether informal exchange emerges or retreat dominates.

Light is social space. It shapes relationships.

Atmosphere is not furnished.

It is designed.

Light Synchronizes Our Biological Rhythm

Human beings are not static systems. Our bodies follow an internal rhythm. Hormones, attention, reaction speed, and body temperature shift throughout the day — and light is the strongest external cue guiding this cycle.

When sufficient activating light reaches the retina in the morning, melatonin levels decrease. The body shifts into a state of readiness. Alertness rises.

If this signal is missing, the day begins with delay. Fatigue lingers. Concentration becomes more difficult.

In the evening, light works in the opposite direction. Warmer, reduced lighting atmospheres signal transition and regeneration.

The problem is that many interiors remain static for hours. Constant lighting conditions ignore our biological rhythm.

The consequences may include:

• persistent daytime fatigue

• reduced ability to concentrate

• disrupted sleep

• increased stress levels

This effect becomes particularly noticeable in work environments with limited access to daylight.

Lighting design that follows the biological rhythm therefore means:

• activating impulses in the morning

• clear visual structure during productive phases

• gentle transitions in the afternoon

And what does this mean for your project?

Not every space can be resolved with standardized lighting concepts or preconfigured scenes. Perception is not generic — and spatial conditions are not either. Architecture, daylight, material surfaces, and patterns of use each create their own psychological situations.

Especially in complex floor plans, multifunctional spaces, or projects with high design ambitions, standard solutions quickly reach their limits.

Psychological impact does not arise from products alone. It emerges from the precise interplay of light, space, and human rhythm. Standards compliant lighting can fulfill technical requirements — but it does not automatically answer how a space feels, how it is processed, or what kind of memory it leaves behind.

Contact Us: